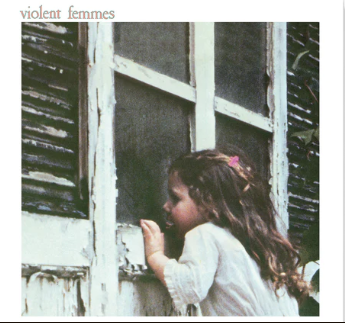

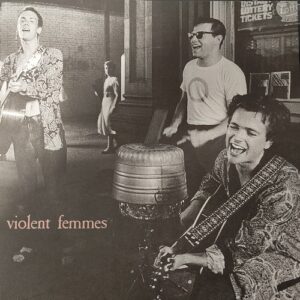

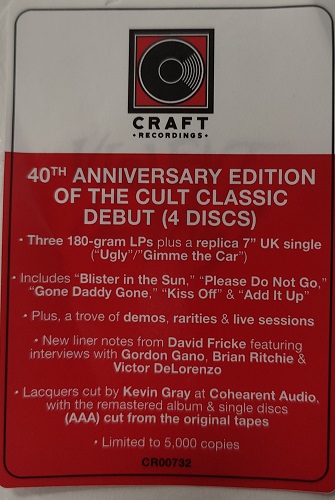

| Title | Violent Femmes 40Th Anniversary (Deluxe) |

|---|---|

| Year | 2024 |

| Labels | Craft Recordings CR00732 |

| Format | Vinyl, CD |

| Length | ??:?? |

| Variants | 4 LP Box Set |

*Expanded Box Set Includes The Full Album, Rare Demos, Live Recordings, and a book featuring archival photos, new linear notes and band interviews.

*Limited to 5000 Copies.

*This Collection of Songs was also released for the 20th Anniversary 2CD Set back in 2003 (excluding Michael feldman interview, Kiss off live)

- a1. blister in the sun

- a2. kiss off

- a3. please do not go

- a4. add it up

- a5. confessions

- b1. prove my love

- b2. promise

- b3. to the kill

- b4. gone daddy gone/ i just want to make love to you

- b5. good feeling

demos

- c1. girl trouble

- c2. breakin’ up

- c3. waiting for the bus

- c4. blister in the sun

- c5. kiss off

- d1. please do not go

- d2. add it up

- d3. confessions

- d4. prove my love

live

- e1. special

- e2. country death song

- e3. to the kill

- e4. never tell

- e5. break song

- e6. her television

- f1. how do you say goodbye

- f2. theme and variations

- f3. prove my love

- f4. gone daddy gone/ i just want to make love to you

- f5. promise

- f6. in style

- f7. add it up

single

- a1. ugly

- b1. gimmie the car

On August 6, 1982, Violent Femmes, a trio from Milwaukee, Wisconsin with an unsettling name and austere, eccentric instrumentation – made their New York debut at the bottom line, opening the two-night engagement headline by punk icons Richard Hell and the Voidoids. Singer-guitarist Gordon Gano, bassist Brian Ritchie, and drummer Victor DeLorenzo had been together for a little over a year and never before performed outside the upper Midwest. But within minutes they owned the room.

“The Violent Femmes don’t just steal the show, they blow a fresh wind of post-punk, originally rooted in rockabilly simplicity, the dry, folk twang of quintessential hobo Dylan and the stark bash and graphic lyricism of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground.” I wrote in a review for Musician Magazine – rare National Ink for a group without an album to promote or, at that point, a record deal. Gano, not yet 20, gripped his Telecaster “with an almost defensive tenacity”, belting frantic edge-of-adulthood tensions in a “cracked, quivering tenor” with “Artful Dodger aura… like Jonathan Richman becoming the Lou Reed he always dreamed of.”

Ritchie was as aggressively forward on the low end. Wielding an oversized acoustic bass guitar typically seen in Mexican mariachi bands, he conducted Gano’s angst and frenzy with the melodic certainty of the Who’s John Entwistle and furious bouts of improvisation. And DeLorenzo was a swinging minimalist on a barely-there kit dominated by an upside-down metal tub, played with brushes for maximum slap and sizzle. The critic Robert Palmer was also at the Bottom Line and raved about Violent Femmes a few days later in “The Pop Life,” his New York Times column. He cited Dylan and the Velvets as well but also skiffle, the British late-fifties variant on American rockabilly, and the sing-along spell of Gano’s songs. “If the major record labels were less financially strapped and more adventurous, this young and extraordinarily talented band would be some artist-development department’s dream-come -true,” Palmer contended. “And they might be anyway, given their catchy material and riveting stage presence.”

I put it another way: “Something better come out soon.” The femmes’ “fatal charms” were “a secret Milwaukee shouldn’t keep to itself.”

Actually, at the time, in that city, Violent Femmes were a phenomenon barely taken seriously, playing more often on the street – under theater marquees, in bus shelters – than in the couple of clubs that would have them. A last minute booking at one of those theatres, The Oriental, on August 23rd, 1981 -suddenly added an opening act to a sold-out concert by the pretenders after the members of that band saw the femmes performing on the sidewalk before showtime – was more irritant than breakthrough. “We still couldn’t get a place to play the next day,” Gano recalls. “And more people were angry at us: How come we got to do that?”

A demo tape recorded after that serendipity, in the fall of ’81, got the Femmes nowhere fast until Alan Betrock, a rock writer and producer who founded the Streetwise Periodical New York rocker, was intrigued enough to fly to Milwaukee and talk with the band about making an album. When Betrock had to pull out, the Femmes were left with a reservation for studio time at a facility in nearby Lake Geneva that was, unbeknownst to them, in receivership. Gear was disappearing between sessions – sold for parts – as the femmes recorded there in July, 1982, thanks to a $10,000 loan that DeLorenzo’s father co-signed for.

Gano, Ritchie and DeLorenzo cut ten songs in a week – all written by the singer and produced by Mark Van Hecke, a friend and composer for theater who engineered the 1981 demo – on a strict budget of live, mostly first takes. “We were using tape, which was expensive, and playing for this record ourselves” Ritchie says today. “We might have a few false starts. We’d get a take, then say, ‘That sounds pretty good, let’s try a few more.’” In the end, the Femmes generally used that first, complete performance.

The Bottom Line shows in August were part of lightning visit arranged by Betrock (who was working with Richard Hell) that included a third night at CBGB. “He wanted people to see us,” Ritchie says gratefully, “thinking somebody might give us a deal – which didn’t happen.” Rejection letters from labels including Columbia and RCA piled up in DeLorenzo’s mailbox, basically with the same message, according to the drummer: “Strange music, wrong haircuts.”

Finally, on April 13th, 1983, Violent Femmes was released by the only record company that didn’t say no: Slash, an offshoot of Los Angeles punk zine. Critical acclaim was immediate – again. Here was an “unnervingly precious debut” by a trio, Rolling Stone contended, “that not only acts like it just reinvented rock & roll but somehow manages to sound like it as well.” A review in the creem called Violent Femmes a “genuine embodiment” of Jonathan Richman’s Stripped-to-essentials ideal for his own group, The Modern Lovers: “We have to learn to play with nothing, with our guitars broken, and it’s raining.”

Record sales slowly, stubbornly followed as Violent Femmes crept to daylight on college radio and the band took its pocket-orchestra magnetism and Gano’s Lyric bravado – the compact turbulence of “blister in the sun”; the staccato peaks and meltdown valleys in “kiss off” and “add it up”; the desperation driving the sixties-pop sunshine in “prove my love” – on the road. “They have no need for the complex writings and trappings of rock,” Britain’s New Musical Express observed during the Femmes first UK tour. “Ramones go Skiffle, son of Lou Reed meets the Modern Lovers and worlds collide.” In March, 1985, with Violent Femmes on its way to gold and eventually platinum status, Gano, Ritchie and DeLorenzo were back at the Oriental Theater – as headliners, their name on the marquee over the words “Sold Out.”

“I never felt any doubts,” Gano claims, citing a quote from the 19th-century philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson that he posted over his bed. “when I was 16 or 17,” as his songwriting went into overdrive: “Do your work, and I shall know you.” “We felt that confident and strong,” Gano argues. “The whole world can say we’re no good. But we know the whole world is wrong.”

“If I put it into a literary frame, Gordon was the William Saroyon of punk rock,” DeLorenzo says, referring to the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and playwright. “He was describing the human condition without being tethered to a particular age of time. That was always one of his strengths – that magic you convey with words.”

The result: a band that seemed to come from nowhere with an album that jumped and jolted like it could have come from any crossroads – CBGB in 1976; the folk-revival Sixties; under a late-fifties moon at Sun Records in Memphis – and ripped the air like new, fearlessly personal history. “In your broken-down kitchen at the top of the stairs/Can I mix in with your affairs/Share a smoke/Make a joke/Grasp and reach for a leg of hope?” Gano pleads in “add it up” sounding like he’s 16 doing on 60 miles an hour, spinning his wheels between first date and last chance – before pouncing into a guitar solo of shredded single-chord frenzy as Ritchie and DeLorenzo rage in kind like a bone-and-sinew clash.

Next door, in creeping-blues gear of “confessions,” trouble and release are in constant seesaw: Gano’s stuttered frustration veering into an instrumental freak-out anchored by Ritchie’s stalking bass.

A second eruption of soloing concludes with Gano’s exhausted sayonara. (“See, I learned my lesson/And I don’t even want to hear about your confessions”) against the dying strum of his guitar, taking one more round on the eerie, main riff. “Somebody once told me, ‘I realized you were a good writer when you made a major chord sound sad,’” Gano says. “I would do interesting stuff musically having no idea I was breaking some kind of rule. I didn’t know enough to know I was doing that.” Ritchie heard Violent Femmes recently at a party and was, he declares, “amazed at how good and distinctive it sounded.” A friend put it on the stereo “to show how out of tune everything was. It drove this guy up the wall. He’s going, ‘Everything is wrong! This is totally out of tune! Did you know that when we when you were making it?’” “We just didn’t care,” the bassist replied. “This is what we were.”

In 1978, Gano – born in New York City and raised in Connecticut until he was 10, when his family moved to Wisconsin – took a trip back to Manhattan to visit an older brother. Gano was 15 and writing songs, channeling his proximity to the church – his father was a Baptist minister – and the country music and Broadway musicals he heard at home into striking contradictions: the cocky transgression of “kiss off”; the deep yearning in “good feeling,” a ballad that became the original side two-finale of Violent Femmes.

But one night in New York, Gano’s brother took him to Max’s Kansas City to see ex-New York Dolls guitarist Johnny Thunders and his band of dissolute rowdies, the Heartbreakers. “That was the top,” Gano says, still excited by the memory. “This was another world. And I was totally down for this world.”

He returned to Milwaukee transported and certain. “That trip,” Gano says, “was confirming – ‘this is what I want to do.’” He also decided to “keep the songs to myself. I had no intention of playing out. I was going to figure things out, then move to New York and get a band going.” But in his senior year of high school, a friend persuaded Gano to do some gigs: coffee shops, open-mic nights at the local clubs. Ritchie saw Gano for the first time at one of those shows, coaxed by a pal who described the singer as “a pint-sized Lou Reed imitator.”

“I was like an old man watching this,” Ritchie says, laughing. “Gordon was playing at his coffeehouse, the Beneath-it-All Cafe. I was probably 20, Gordon was 17 or 18. But he was amazing. And he had a huge stash of songs, 50 or 60 of them” – including everything that ended up on Violent Femmes and the 1984 follow-up, Hallowed Ground. When he and Gano met some time later at a punk club, “Gordon said, ‘I’m playing at my school tomorrow. Would you like to play with me?’” Gano and Ritchie turned up at Rufus King High School for a National Honor Society Induction Ceremony where Gano was among the honorees – almost. As part of the talent program, “We were going to do ‘Good Friend,’” Ritchie recalls, ”but changed our minds.” They played “Gimme the Car” instead, a manic, sexually blunt rocker that cost Gano his NHS medal and, Ritchie says, “got him kicked out of school.”

DeLorenzo – an actor and Ritchie’s “drummer of choice” in Milwaukee – was out of town, on tour with a theater company. But as soon as he returned, Ritchie took him to see Gano at the Beneath-It-All Café. The three played together for the first time there, Ritchie and DeLorenzo – nearly a decade older than the singer – sitting in on banjo and a snare drum, respectively.

“It took off immediately,” Ritchie says. He and DeLorenzo were made-to-order rhythm section with a mutual love of free jazz and big ears for mischief. Ritchie started playing his signature mariachi bass after trying to invent a guitar with that range and tone – putting bass strings and tuning pegs on a conventional, acoustic model. DeLorenzo came up with his “trranceaphone” – the tub placed over a floor tom for greater resonance – while the two played together in the Trance and Dance band. They were also huge fans of the twang and au naturel drive of a 1958 album, Gene Vincent Rocks!! And the blue caps roll!! Play it next to Violent Femmes, DeLorenzo says – especially Vincent’s two-minute grenade “Flea Brain” – and you can “hear how we got this idea of rhythm section that doesn’t have to be electric bass and a full drum set.”

Violent Femmes – a name coined by Ritchie and first used with DeLorenzo when they were a duo for hire – played on the streets because (a) Clubs would not hire them and (b) It was too hot in Milwaukee, in the summer of ’81, to rehearse in DeLorenzo’s basement. Ritchie and DeLorenzo had previously worked outdoors with local busker named Doorway Dave. “But what we found was that Gano’s vocals came out really well on the street, with the acoustic backing,” Ritchie says. “If we had been pounding rock band, you wouldn’t have heard the words.” Even worse, “We would have sounded like other people.”

“It did a lot for us,” Gano concurs. “It shaped the dynamics of our performing,” and, he points out, inspired details in the arrangements such as Gano’s guitar break in “Prove My Love,” which evokes Pete Townsend’s Power Chord spasms on the 1965 Who Single “Anyway, Anyhow, anywhere.” “I thought if I’m playing single notes on the street, nobody’s going to hear it,” Gano explains. “So, I hit it as hard as I could, to get some contrast with Brian and Victor as they made their shift in the next part, paring it down.”

Not the Milwaukee, for the most part, noticed or cared. “Brian and Victor had played a lot – there were people they knew from other bands,” Gano says. “More often than not, they would cross the street and pretend not to see or hear us. We were considered an embarrassment. What we were doing was not cool.”

“The way the Violent Femmes have fashioned a unique, arresting style out of such disparate influences,” I wrote that musician review, “comes through with the brutal clarity on one rolling, campfire ballad about a mentally disturbed father who murders the daughter he loves.” “Country Death’s song” was a jet-black whiplash at the Bottom Line, packing echoes of Johnny Cash, Woody Guthrie, and the talking- blues Dylan. And it was one of Gano’s earliest, original songs. This reissue includes a performance from September, 1981 at the Beneath-It-All Cafe. But the Femmes did not record it for their first LP.

Gano credits Richie with the focused and momentum of Violent Femmes, “He said, ‘Let’s keep it a rock album.’” – tight, taut, explosive. “His thought was, ‘We’re planning a career. Let’s explore the country, gospel and jazz on a future album.’” “Country Death Song” would be the opening track on Hallowed Ground. Other songs then around in live and demo form and resurrected on later albums: “Never Tell” (Hallowed Ground); “Special” (1986’s The Blind Leading the Naked) and “Girl Trouble” (1991’s Why Do Birds Sing?).

“We had a prototype for the record and followed that,” Ritchie says. “We had the order and everything, what songs would be on there. We did not record anything else.” The ‘81 demos “sound almost identical to the album. But we had this corny idea that you go into a studio to make a record. If we had more guts and just went DIY, who knows what might have happened.”

“Gordon had a wealth of material in this famous notebook of his,” DeLorenzo says. “It was just a matter of Brian and I applying our arranging skills to the chord structures and melodies Gordon would bring us.” It was “a definite choice, what songs ended up on the album. Those ten made a nice collection, and the sequence worked really well.”

Issued in a year of Landmark Studio debuts by R.E .M. (Murmur), Metallica (Kill ‘Em All) and Sonic Youth (Confusion is Sex) as well as quantum leaps by U2 (War) and the Replacements (Hootenanny), Violent Femme sounds like nothing else of its time or any other: an insurrection wired for joy; its skeletal fury improbably dense with experiment, songcraft, trap-door wit and those hard, adolescent truths that can last a lifetime. “We’re avant-garde because we’re so reactionary,” Ritchie claimed in the band’s first Rolling Stone story, published in May, 1983. “We go back to improvisation, to raw emotions and primitive, old-fashioned sounds. And Gordon’s songs make the whole thing accessible.”

Hooks turn into chaos on Violent Femmes – and back again. Gano seems like he’s struggling to get his despair across in “please do not go,” Street-Corner Reggae that comes with a Ritchie bass solo suggesting bebop Paul McCartney. The mad duality of “To the Kill” – blasts of free improvisation with a bent-disco center that Ritchie calls “Gordon’s idea of funky” – comes right after “Promise’” a pop-art vengeance Neil Young might have written for Buffalo Springfield.

The Femmes were astute classicists. Gano paraphrases a vocal cue from a 1965 Herman’s Hermits single “I’m Henry VIII, I Am” in “prove my love” (“Third verse, same as the first”) and borrows a blues-lion bridge in “I just want to make love to you” – A Willie Dixon song recorded by Muddy Waters in 1954 – for the hurt and missing in “Gone Daddy Gone.” “I told Gordon, ‘You’re going to get in trouble for this,’” says Ritchie, who frames Gano’s vocal anxiety with the galloping exotica of Xylorimba, a xylophone-marimba hybrid. “He said, ‘nobody’s going to hear the record anyway.’” (Dixon ultimately got his name and title on the album.)

But what often seems like pure impulse – musical and lyrical asides minted on the spot – was decisive and rehearsed. DeLorenzo’s drum break in the hurtling haiku of “Blister in the Sun” “happened the first time we played the song,” Ritchie says. “Gordon played the riff, we were trying to figure out what was next, and immediately Victor did that. Then “in the process of playing it hundreds of times, that’s what you hear on the recording.”

Gano was specific in his writing. “I can’t recall anything,” he says, “that I adlibbed in any way on that first album. It was all planned.” His immortal sing-song line in “Kiss Off” (“I hope you know this is going down on your permanent record”) was in place on the 1981 demo. So was the countdown of agony that comes after (“One ‘cause you left me… six for my sorrow”) and the mind freeze when he gets to eight. “That’s the way I wrote it – this voice getting so carried away that he forgets what eight is for.”

40 years later, violent femmes is slippery, enduring perfection: rich in colliding influences but of no fixed genre; made with the bare necessities transformed by imagination, comic spirit and a wickedly articulate candor; forged indifference and hostility yet tenacious in purpose and execution. “It exists as an artifact of history,” says DeLorenzo, who left the band in 1993 and has returned twice in the 2000s. “At the same time, it’s been passed down from generation to generation which continues to make it brand new. “We’re in a ratified position with that record.”

Gano and Ritchie will play every song on violent femmes when they tour for its 40th anniversary. They play virtually every song anyway when they go out as the femmes. “Some things become so popular, identified within certain sounds,” Gano says, “that they become dated, iconic of that period. Our record doesn’t do that at all. I feel like every song still has this possibility – where it could completely change at any moment.” “We were intentionally trying to stand outside the times,” Ritchie declares. “And the music, the writing – it was authentic. There’s something almost literary about the songs in that order.”

Talking to NME in 1986, the bassist summed up Violent Femmes’ mission and achievement this way: “Our goal isn’t to give them what they want,” he said of their audiences. “Our goal is to give them the things that they don’t even know existed before.” Violent femmes was the first and is still the only record of its kind. And it has never left.

David Fricke.

This Compilation (P) & (C) 2024 Craft Recordings.

Manufactured and distributed by Concord, 10 Lea Avenue, Suite 300, Nashville TN 37210.

All Rights reserved, Unauthorized Duplication is a violation of Applicable laws. Made in Czech Republic. CR00732